A robot is defined as Holonomic if the number of its Controllable Degrees of Freedom (CDOF) is equal to the Total Degrees of Freedom (TDOF) in its configuration space.

A holonomic robot has complete and independent control over all its movement directions. Holonomic robots can move in any direction forward, backward, or sideways and spin in place, all at the same time.

Think about the difference between driving your car and playing a video game. Most real-world vehicles, like your car, are non-holonomic: they cannot slide sideways. Your steering and throttle movements are constrained by the way the wheels roll, forcing you to perform complex turns and backups to park. It has to face the direction it wants to move. A holonomic robot faces no such restriction. If it needs to move 5 cm to the left, it just slides 5 cm to the left, instantly without turning.

1. What does “Holonomic” actually mean?

A holonomic robot allows you to control forward motion, sideways motion, and rotation independently and simultaneously. It can move sideways, forward, backward, and rotate independently.

In robotics research, specifically in the field of Kinematics (the study of motion), we define robots based on their constraints.

According to standard robotics literature, such as Modern Robotics (Lynch & Park) or the Springer Handbook of Robotics, here is the formal definition:

“A robot is defined as Holonomic if the controllable degrees of freedom are equal to the total degrees of freedom in its configuration space.”

In robotics, we consider three primary directions of motion for a robot on a flat floor:

- Translation (X): Moving forward and backward.

- Translation (Y): Moving left and right (strafe).

- Rotation (Angle): Spinning in place.

Imagine you want to move 5 CM directly to your left:

- Non-Holonomic Robot: Imagine you have to parallel park a car. The car must use both its X (forward/backward) and Rotation (Angle) movements. It has to turn its wheels, drive forward slightly, and then turn the wheels back again. It cannot just slide sideways.

- Holonomic Robot: Now comes the holonomic robot. Its wheels instantly combine their forces to push the robot purely sideways. Crucially, the robot’s Angle (where it is facing) and its X position are completely unchanged. This total separation of movement control is the definition of holonomic motion.

In a 2D world (like a robot moving on a gym floor), there are exactly three ways to move (3 Degrees of Freedom):

- Surge: Moving forward and backward (X-axis).

- Sway: Moving left and right (Y-axis).

- Yaw: Rotating in a circle (Angle).

The Non-Holonomic Example (Your Car):

A car has a motor (forward/back) and a steering wheel (rotation). It cannot move sideways directly. To park parallel, you have to do a complex series of forward and backward moves.

- Total Degrees of Freedom: 3 (X, Y, Angle)

- Controllable Degrees of Freedom: 2 (Gas, Steering)

- Result: Non-Holonomic (Restricted).

In robotics, the definition relies on comparing a robot’s Controllable Degrees of Freedom (CDOF) to its Total Degrees of Freedom (TDOF).

- Total Degrees of Freedom (TDOF): This is the total number of ways the robot can move in the space it occupies. Since our robot is on a flat floor, the TDOF is 3: forward/backward, left/right, and rotation.

- Controllable Degrees of Freedom (CDOF): This is the number of movements you can command independently at any given moment.

For a system to be Holonomic, the two must be equal: TDOF = CDOF (3 = 3).

2. Common wheel and drive types

You cannot build a holonomic robot with normal tires. Normal tires have high friction to stop you from sliding sideways. To get holonomic movement, we have to manipulate friction vectors using special wheels.

The entire idea relies on making specialized wheels that can be driven in combinations to produce a single, unified force. The robot controls the speed and direction of each wheel individually. By telling some wheels to push and others to pull, the internal forces cancel each other out in one axis (like the forward push) but combine in another axis (like the sideways push). This clever arrangement allows the robot to generate a resultant force pointing in any direction, giving it total freedom of movement.

1. Omni-Wheels

These wheels have rollers mounted at a 90-degree angle to the main wheel direction. They allow the robot to roll forward normally, but if a sideways force is applied, the rollers simply slide along the floor. This lets the robot move in a straight line while its wheels are angled, or it can be pushed sideways without friction.

The main wheel powers the robot forward. But if the robot gets pushed from the side, the little rollers spin freely, letting the robot slide without friction, fighting back.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Simple & Cheap: Very basic construction. | No Pushing Power: If you try to push sideways, the rollers just spin. |

| Smooth Movement: Generally smoother than Mecanum wheels. | Gap Risk: Gaps between rollers can cause bumps. |

| Flexible Design: Can be used in 3-wheel (triangle) or 4-wheel setups. | Awkward Mounting: Usually needs to be mounted at a 45-degree angle on the frame. |

Application: Omni wheels are popular in small mobile robots and the robot soccer (RoboCup) league, where speed and quick direction changes are more important than pushing power. They are also used in conveyor systems to slide boxes in different directions.

2. Mecanum Wheels

These are the most common types. They look like normal tires but have a series of free-spinning rollers attached to their circumference at a 45-degree angle. This clever design allows the forces from the spinning wheel to cancel out in one direction (forward) and combine in the other (sideways), enabling true strafing.

Invented by Bengt Ilon in the 1970s, these are the most popular choice for competitive robotics (like FIRST Tech Challenge).

Mecanum wheels have rollers attached at a 45-degree angle. This angle is critical. When the wheel spins, it doesn’t just push the robot forward; it pushes it forward and diagonally.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Easy to Build: They mount parallel like normal car wheels. | Low Traction: The rollers slip easily, making them bad for ramps or pushing. |

| Agile: Excellent omnidirectional movement. | Bumpy Ride: The rollers can vibrate on hard floors. |

| Compact: Doesn’t require extra steering motors. | Complex Code: Needs precise vector math to control correctly. |

Application: You will often see these in tight warehouse environments where forklifts need to maneuver sideways between narrow aisles. They are also the standard choice for robotics competitions (like FIRST Tech Challenge) because they are easy to assemble.

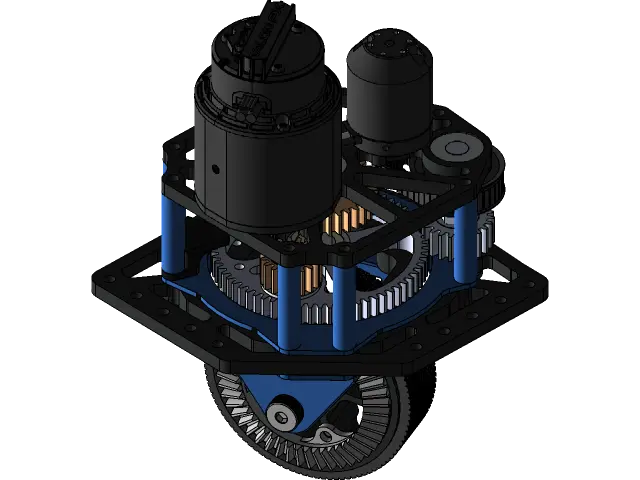

3. Swerve Drive

The swerve drive is conceptually different. It doesn’t use slippery rollers. Instead, every single wheel on the robot is an active caster. They use four individual wheel modules, where each module has its own motor for driving and a separate motor for steering. To move sideways, the robot simply commands all four wheels to rotate 90 degrees and then drives forward, achieving perfect strafing with maximum grip. It uses standard rubber tires, so it has much more pushing power (traction) than Omni or Mecanum wheels.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| High Traction: Uses normal rubber tires, so it has great grip. | Expensive: Requires 8 motors (4 drive + 4 steer) and complex gearboxes. |

| Powerful: Can push heavy loads while strafing. | Heavy: All those motors add a lot of weight. |

| Precise: Extremely accurate movement control. | Difficult to Build: Mechanically complex and hard to maintain. |

Application: Swerve is the “gold standard” for high-end industrial AGVs (Automated Guided Vehicles) that move heavy car parts or machinery. It is also the dominant drivetrain in top-tier FRC (First Robotics Competition) teams due to its unbeatable combination of power and agility.

3. Advantages and Disadvantages of Holonomic Robots

If these robots are so cool, why don’t we have Holonomic cars?

While the specific wheels have their own trade-offs, here is a summary of the general advantages and disadvantages you get whenever you choose a holonomic design over a traditional non-holonomic one:

| Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|

| Maneuverability: Can navigate extremely tight or complex environments quickly by moving sideways or diagonally without pausing. | Reduced Traction/Pushing Power: The specialized wheels (Mecanum/Omni) often rely on rollers, which lowers the contact surface area and makes the robot easier to push around or slip on ramps. |

| Simplified Path Planning: The software only needs to calculate the final position, not the complex sequence of turns required to get there (like a three-point turn). | Higher Mechanical Complexity: They require more motors (often four instead of two) and more sophisticated mechanical linkages compared to simple wheeled robots. |

| Efficient Movement: The robot can always take the shortest possible path between two points, even if it’s sideways. | More Complex Programming: The code to translate joystick input into the correct speed for each of the four individual wheels can be computationally intensive and harder to debug. |

Holonomic robots offer maximum freedom, making them perfect for tasks that require surgical precision in confined spaces. However, that freedom comes at the cost of simplicity, strength, and traction, meaning they are not ideal for tasks that require high speed over rough terrain or a lot of pushing power.

4. Frequently Asked Questions

I have analyzed the most common queries regarding holonomic robots on search engines and forums like StackExchange. Here are the answers, detailed for a high school physics level.

1. Is a drone a holonomic robot?

Generally, no. A standard quadcopter drone is under-actuated. To move forward, it must tilt (pitch) forward. To move sideways, it must roll sideways. It cannot maintain a perfectly flat hover and slide sideways at the same time. The movement is coupled with its orientation (tilt), making it technically non-holonomic in 6D space.

2. Why don’t we use holonomic wheels on cars?

Three reasons: Friction, Complexity, and Cost.

- Friction: Omni and Mecanum wheels have very low traction. If you put them on a Honda Civic, you couldn’t drive up a steep hill; the rollers would just spin.

- Suspension: These wheels need a perfectly flat floor. A pothole would destroy a Mecanum wheel mechanism.

- Safety: At 60mph, you want your car to go straight. If a car could accidentally slide sideways on the highway, it would be incredibly dangerous.

3. What is the difference between Omnidirectional and Holonomic?

This is a common point of confusion.

- Omnidirectional: Means the robot can move in any direction.

- Holonomic: Relates to the controllability of that movement.

- Nuance: A car is NOT omnidirectional (it can’t move sideways). A Swerve Drive robot is both Omnidirectional and Holonomic. However, some researchers argue that if a robot has to stop and steer its wheels before moving (like a slow swerve drive), it is not truly holonomic in the instantaneous sense, though broadly speaking, the terms are often used interchangeably in high school robotics.

4. Which is better: 3 wheels or 4 wheels?

- 3 Wheels (Triangular/Kiwi): Cheaper and ensures all wheels touch the ground (because 3 points define a plane). However, it is less stable and has less pushing power.

- 4 Wheels: More stable and faster, but requires suspension. If the floor is uneven, one wheel might lift off the ground, causing the robot to spin uncontrollably.

5. Is a tank drive robot holonomic?

No. A tank drive (skid steer) can turn in place (spin), but it cannot strafe sideways. It must rotate to face a new direction before moving there. Therefore, it is non-holonomic.

5. References

- Lynch, K. M., & Park, F. C. (2017). Modern Robotics: Mechanics, Planning, and Control (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. (Provides the foundational kinematic definitions of holonomic and non-holonomic constraints.)

- Ilon, B. E. (1975). Wheel structure. U.S. Patent 3,876,255. (The original patent for the Mecanum wheel, detailing the core concept of angled rollers to generate lateral force.)

- Vector Kinematics: The mathematical principle of vector addition used to analyze and control the resulting direction and speed of mobile robots with multiple wheels.

- Applied Differential Geometry: The mathematical framework used to formally analyze and prove the integrability (holonomic) or non-integrability (non-holonomic) of a mobile robot’s motion constraints